State Telemedicine Gaps Analysis Coverage &; Reimbursement

State By State comparison of improved coverage and reimbursement of telemedicine adoption

January 19, 2016 by Latoya Thomas and Gary Capistrant

Executive Summary

Payment and coverage for services delivered via telemedicine are some of the biggest challenges for telemedicine adoption. Patients and health care providers may encounter a patchwork of arbitrary insurance requirements and disparate payment streams that do not allow them to fully take advantage of telemedicine.

The American Telemedicine Association (ATA) has captured the complex policy landscape of 50 states with 50 different telemedicine policies, and translated this information into an easy to use format. This report complements our 50 State Gaps Analysis: Physician Practice Standards & Licensure, and extracts and compares telemedicine coverage and reimbursement standards for every state in the U.S. ultimately leaving each state with two questions:

- “How does my state compare regarding policies that promote telemedicine adoption?”

- “What should my state do to improve policies that promote telemedicine adoption?”

Using data categorized into 13 indicators related to coverage and reimbursement, our analysis continues to reveal a mix of strides and stagnation in state-‐based policy despite decades of evidence-‐based research highlighting positive clinical outcomes and increasing telemedicine utilization.

Since our initial report in September 2014 11 states and D.C. have adopted policies that improved coverage and reimbursement of telemedicine-‐provided services, while two states have adopted policies further restricting coverage (Figure 1).1

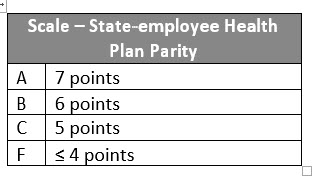

States have made efforts to improve their grades through the removal of arbitrary restrictions and adoption of laws ensuring coverage parity under private insurance, state employee health plans, and/or Medicaid plans, as indicated in Figure 2. Overall, there are more states now with above average grades, “A” or “B”, including Iowa which improved from an ‘F’ to ‘B’, than reported in September 2014.

In recent months, five states (Delaware, Iowa, Mississippi, Nevada, and Oklahoma) have higher scores suggesting a supportive policy landscape that accommodates telemedicine adoption while one state saw a drop in their composite grade. New Hampshire dropped from an ‘A’ to ‘B’ as a result of adopted legislation that includes Medicaid telehealth coverage language similar to Medicare. Despite the adoption of a private insurance parity law earlier this year, Connecticut, like Rhode Island, continues to average the lowest composite score suggesting many barriers and little opportunity for telemedicine advancement (Table 1).

When broken down by the 13 indicators, the state-‐by-‐state comparisons reveal even greater disparities.

- Eight states have enacted telemedicine parity laws since the initial report in 2014. Of the 29 states that have telemedicine parity laws for private insurance, 22 of them and

- scored the highest grades indicating policies that authorize state-‐wide coverage, without any provider or technology restrictions (Figure 3). Less than half of the country, 22 states, ranked the lowest with failing scores for having either no parity law in place or numerous artificial barriers to parity. This is a significant improvement as more states adopt parity law Arkansas maintains a failing grade because it places arbitrary limits in its parity law.

- Forty-‐eight state Medicaid programs have some type of coverage for telemedicine. Only eight states and D.C. scored the highest grades by offering more comprehensive coverage, with few barriers for telemedicine-‐provided services (Figure 4). Delaware, Iowa, Nevada, and Oklahoma passed reforms that ensure parity coverage with little or no restric Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and West Virginia ranked the lowest with failing scores in this area. New Hampshire dropped from an ‘A’ to ‘B’ as a result of adopted legislation that includes Medicaid telehealth coverage language similar to Medicare.

- Another area of improvement includes coverage and reimbursement for telemedicine under state employee health plans. Twenty-‐six states have some type of coverage for telehealth under one or more state employee health plan. Most states self-‐insure their plans thus traditional private insurer parity language does not automatically affect them. Oregon is an exception which amended its parity law this year to include self-‐

insured state employee health plans. 50 percent of the country is ranked the lowest with failing scores due to partial or no coverage of telehealth (Figure 5).

Regarding Medicaid, states continue to move away from the traditional hub-‐and-‐spoke model and allow a variety of technology applications. Twenty-‐six states and D.C. do not specify a patient setting as a condition for payment of telemedicine (Figure 6). Aside from this, 36 states recognize the home as an originating site, while 18 states recognize schools and/or school-‐ based health centers as an originating site (Figures 7-‐8).

Vermont improved a letter grade because it now covers home remote patient monitoring. Half of the country ranks the lowest with failing scores either because they only cover synchronous only or provide no coverage for telemedicine at all. Idaho, Missouri, North Carolina and South Carolina prohibit the use of “cell phone video” to facilitate a telemedicine encounter (Figure 9).

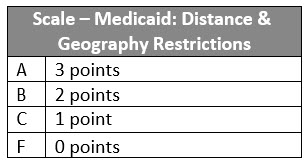

There is still a national trend to allow state-‐wide Medicaid coverage of telemedicine instead of focusing solely on rural areas or designated mileage requirements (Figure 10).

States are also increasingly using telemedicine to fill provider shortage gaps and ensure access to specialty care. Seventeen states and D.C. do not specify the type of healthcare provider allowed to provide telemedicine as a condition of payment (Figure 11). While 20 states ranked the lowest with failing scores for authorizing less than nine health provider types. Florida, Idaho, and Montana ranked the lowest with coverage for physicians only.

Overall, coverage of specialty services for telemedicine under Medicaid is a checkered board and no two states are alike.

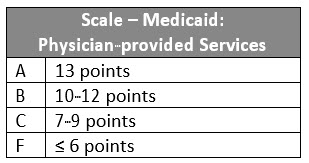

- Ten states and D.C. rank the highest for coverage of telemedicine-‐provided physician services and most states cover an office visit or consultations, with ultrasounds and echocardiograms being the least covered telemedicine-‐provided services (Figure 12).

- For mental and behavioral health services, generally mental health assessments, individual therapy, psychiatric diagnostic interview exam, and medication management are the most covered via telemedicine. Twelve states and D.C. rank the highest for coverage of mental and behavioral health services (Figure 13). The lowest ranking states for all Medicaid services, scoring an ‘F’, are Connecticut and Rhode Island which have no coverage for telemedicine under their Medicaid plans.

- Although state policies vary in scope and application, five more states have expanded coverage to include telerehabilitation. Seventeen states are known to reimburse for telerehabilitative services in their Medicaid plans. Of those, 11 states rank the highest with telemedicine coverage for therapy services (Figure 14).

- Alaska is the only state with the highest ranking for telemedicine provided services under the home health benefit (Figure 15). Seventy percent of the country ranked the

lowest with failing scores due to a lack of telemedicine services covered under the home health benefit.

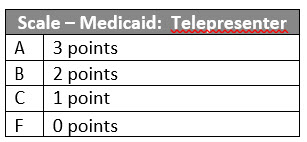

Finally, twenty-‐seven states have unique patient informed consent requirements for telemedicine encounters (Figure 16). Twenty-‐two states do not require a telepresenter during the encounter or on the premises (Figure 17).

PURPOSE

Patients and health care enthusiasts across the country want to know how their state compares to other states regarding telemedicine. While there are numerous resources that detail state telemedicine policies, they lack a state-‐by-‐state comparison. ATA has created a tool that identifies state policy gaps with the hope that states will respond with more streamlined policies that improve health care quality and reduce costs through accelerated telemedicine adoption.

This report fills that gap by answering the following questions:

- “How does my state’s telemedicine policies compare to others?”

- “Which states offer the best coverage for telemedicine provided services?”

- “Which states impose barriers to telemedicine access for patients and providers?”

It is important to note that this report is not a “how-‐to guide” for telemedicine reimbursement. This is a tool aimed to serve as a reference for interested parties and to inform future policy decision making. The results presented in this document are based on information collected from state statutes, regulations, Medicaid program manuals/bulletins/fee schedules, state employee handbooks, and other federal and state policy resources. It is ATA’s best effort to interpret and understand each state’s policies. Your own legal counsel should be consulted as appropriate.

OVERVIEW

State lawmakers around the country are giving increased attention to how telehealth can serve their constituents. Policymakers seek to reduce health care delivery problems, contain costs, improve care coordination, and alleviate provider shortages. Many are using telemedicine to achieve these goals.

Over the past four years the number of states with telemedicine parity laws – that require private insurers to cover telemedicine-‐provided services comparable to that of in-‐person – has doubled.2 Moreover, Medicaid agencies are developing innovative ways to use telemedicine in their payment and delivery reforms resulting in 48 state Medicaid agencies with some type of coverage for telemedicine provided-‐services.

Driving the momentum for telemedicine adoption is the creation of new laws that enhance access to care via telemedicine, and the amendment of existing policies with greater implications. Patients and health care providers are benefitting from policy improvements to existing parity laws, expanded service coverage, and removed statutory and regulatory barriers. While there are some states with exemplary telemedicine policies, lack of enforcement and general awareness have led to a lag in provider participation. Ultimately these pioneering telemedicine reforms have trouble reaching their true potential.

Other areas of concern include states that have adopted policies which are limiting in scope or prevent providers and patients from realizing the full benefits of telemedicine. Specifically, artificial barriers such as geographic discrimination and restrictions on provider and patient settings and technology type are harmful and counterproductive.

ASSESSMENT METHODS

Scoring

This report considers telemedicine coverage and reimbursement policies in each state based on two categories:

- Health plan parity

- Medicaid conditions of payment.

These categories were measured using 13 indicators. The indicators were chosen based on the most recent and generally accessible information assembled and published by state public entities. Using this information, we took qualitative characteristics based on scope of service, provider and patient eligibility, technology type, and arbitrary conditions of payment and assigned them quantitative values. States were given a certain number of points for each indicator depending on its effectiveness. The points were then used to rank and compare each state by indicator. We used a four-‐graded system to rank and compare each state. This is based off of the scores given to each state by indicator. Each of the two categories was broken down into indicators – three indicators for health plan parity and 10 indicators for Medicaid conditions of payment.

Each indicator was given a maximum number of points ranging from 1 to 35. The aggregate score for each indicator was ranked on a scale of A through F based on the maximum number of points.

The report also includes a category to capture innovative payment and service delivery models implemented in each state. In addition to state supported networks in specialty care and correctional health, the report identifies a few federally subsidized programs and waivers that states can leverage to enhance access to health care services using telemedicine.

Limitations

Telemedicine policies in state health plans vary according to a number of factors – service coverage, payment methodology, distance requirements, eligible patient populations and health care providers, authorized technologies, and patient consent. These policy decisions can be driven by many considerations, such as budget, public health and safety needs, available infrastructure or provider readiness.

As such, the material in this report is a snapshot of information gathered through December 2015. The report relies on dynamic policies from payment streams that are often dissimilar and unaligned.

Illinois and Massachusetts have enacted “If, then” telemedicine coverage laws which prevent the enforcement of discriminatory practices such as an in-‐person encounter.34 “If” the state regulated plan chooses to cover telemedicine-‐provided services, “then” the plan is prohibited from requiring an in-‐person visit. ATA does not interpret these statutes as parity laws.

We analyzed both Medicaid fee-‐for-‐service (FFS) and managed care plans. Benefit coverage under these plans vary by size and scope. We used physician, mental and behavioral health, home health, and rehabilitation services as a benchmark for our analysis. Massachusetts and New Hampshire do not cover telemedicine-‐provided services under their FFS plans but do have some coverage under at least one of their managed care plans. As such, the analysis and scores are reflective of the telemedicine offerings in each program, and not the Medicaid program itself, regardless of size and scope.

We did not analyze state Children’s Health Insurance Plans (CHIP) plans. We are aware that states provide some coverage of telemedicine-‐provided services for CHIP beneficiaries.

Additionally, some states recognize schools and/or school-‐based health centers as originating sites, however we did not separately score or rank school-‐based programs.

Although two states include coverage of telemedicine-‐provided services under worker’s compensation plans, we did not analyze this coverage benefit. ATA may include these plans in future versions of this report as states extend coverage to include telemedicine under worker’s compensation and disability insurance.

Other notable observations in our analysis include state Medicaid plans that do not cover therapy services (i.e. physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech language pathology).5 States with no coverage for these benefits were not applicable for scoring or ranking.

Additionally, some states policies can be conflicting. States like Arkansas and New York have enacted laws requiring telemedicine parity in their Medicaid plans. However, regulations and Medicaid provider manuals do not reflect all of these policy changes. In those cases, the analysis and scores are reflective of the authorized regulations and statutes enacted by law unless otherwise noted. Future reports will reflect changes in the law if applicable.

Also, this report is about what each state has “on paper”, not necessarily in service. Important factors, such as the actual provision and utilization of telemedicine services and provider collaboration to create service networks are beyond the scope of this report.

Indicators

Parity

A. Private Insurance

Full parity is classified as comparable coverage for telemedicine-‐provided services to that of in-‐ person services. Twenty-‐eight states and the District of Columbia have enacted full parity laws. Only Arizona has enacted a partial parity law that requires coverage and reimbursement, but limits coverage to a certain geographic area (e.g., rural) or a predefined list of health care services. Since our initial report, some parity laws have included restrictions on patient settings. For this report’s purpose, we added this component to our methodology, and continue to measure other components of state policies that enable or impede parity for telemedicine-‐provided services under private insurance health plans.

States with the highest grades for private insurance telemedicine parity provide state-‐wide coverage, and have no provider, technology, or patient setting restrictions (Figure 3). Among states with parity laws, Arizona, New York, and Vermont scored about average (C). New York and Vermont lawmakers have placed patient setting restrictions on those services eligible for coverage parity. While Arizona continues to limit coverage to interactive audio-‐video only modalities and the types of services and conditions that are covered via telemedicine. Despite enacting a parity law in March 2015, Arkansas maintains a failing grade because it places arbitrary limits on patient location, eligible provider type, and requires an in-‐person visit to establish a provider-‐patient relationship. Forty-‐four percent of the country ranks the lowest with failing (F) scores, a drop from the initial report.

B. Medicaid

Each state’s Medicaid plan was assessed based on service limits and patient setting restrictions. Other components assessed for all three plans include provider eligibility and the type of technology allowed were also examined to determine the state’s capacity to fully utilize telemedicine to overcome barriers to care. For this report’s purpose, we measured components of state policies that enable or impede parity for telemedicine-‐provided services under Medicaid plans.

Forty-‐eight state Medicaid programs have some type of coverage for telemedicine.

Eight states and D.C. have the highest grades for Medicaid coverage of telemedicine-‐provided services (Figure 4). Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and West Virginia ranked the lowest with failing (F) scores. Iowa, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Washington have all made improvements to expand coverage of telemedicine for their Medicaid populations. Connecticut and Rhode Island are the only states without coverage for telemedicine under their Medicaid plans. Of the 48 states with coverage, Idaho offers the least amount of coverage for telemedicine-‐provided services. While Hawaii, Idaho, New Hampshire, and West Virginia still apply geography limits in addition to restrictions on service coverage, provider eligibility, and patient setting.

C. State Employee Health Plans

We measured components of state policies that enable or impede parity for telemedicine-‐ provided services under state-‐employee health plans. Most states self-‐insure their plans therefore traditional private insurer parity language does not automatically affect them.

Oregon is an exception which amended its parity law this year to include self-‐insured state employee health plans.

Twenty-‐six states provide some coverage for telemedicine under their state employee health plans with 26 states extending coverage under their parity laws (Figure 5). Most states self-‐ insure their plans and 50 percent of the country is ranked the lowest with failing scores due to partial or no coverage of telehealth.

Medicaid Service Coverage & Conditions of Paymeny

D. Patient Setting

In telemedicine policy, the place where the patient is located at the time of service is often referred to as the originating site (in contrast, to the site where the provider is located and often referred to as the distant site). The location of the patient is a contentious component of telemedicine coverage. A traditional approach to telemedicine coverage is to require that the patient be served from a specific type of health facility, such as a hospital or physician’s office.

Left out by these approaches are the sites where people predominantly spend their time, such as homes, office/place of work, schools, or traveling around. With advances in decentralized computing power, such as cloud processing, and mobile telecommunications, such as 4G wireless, the current approach is to cover health services to patients wherever they are.

For this report, we measured components of state Medicaid policies that, for conditions of coverage and payment, broaden or restrict the location of the patient when telemedicine is used. The following sites are observed as qualified patient locations:

- Hospitals

- doctor’s office

- other provider’s office

- dentist office

- home

- federally qualified health center (FQHC)

- critical access hospital (CAH)

- rural health center (RHC)

- community mental health center (CMHC)

- sole community hospital

- school/school-‐based health center (SBHC)

- assistive living facility (ALF)

- skilled nursing facility (SNF)

- stroke center

- rehabilitation/therapeutic health setting

- ambulatory surgical center

- residential treatment center

- health departments

- renal dialysis centers

- habilitation centers.

States received one (1) point for each patient setting authorized as an eligible originating site. Those states that did not specify an originating site were given the maximum score possible (20).

Twenty-‐six states and D.C. do not specify a patient setting or patient location as a condition of payment for telemedicine (Figure 6).

Aside from this, 36 states allow the home as an originating/patient site, while 18 states recognize schools and/or SBHCs as an originating site (Figures 7-‐8).

Six states ranked the lowest with failing (F) scores for designating less than six patient settings as originating sites with Florida and New Jersey ranking the lowest with only two eligible originating sites.

E. Eligible Technologies

Telemedicine includes the use of numerous technologies to exchange medical information from one site to another via electronic communications. The technologies closely associated with services enabled by telemedicine include videoconferencing, the transmission of still images (also known as store-‐and-‐forward), remote patient monitoring (RPM) of vital signs, and telephone calls. For this report, we measured components of state Medicaid policies that allow or prohibit the coverage and/or reimbursement of telemedicine when using these technologies.

Seven states score above average on our scale with Alaska taking the highest ranking (Figure 9). The state covers telemedicine when providers use interactive audio-‐video, store-‐and-‐forward, remote patient monitoring, and audio conferencing for some telemedicine encounters. Alaska, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, and Texas all cover telemedicine when using synchronous technology as well as store-‐and-‐forward and remote patient monitoring in some capacity. Fifty percent of the states rank the lowest with failing (F) scores either because they only cover synchronous only or provide no coverage for telemedicine at all.

Further, Idaho, Missouri, North Carolina and South Carolina prohibit the use of “cell phone video” or “video phone” to facilitate a telemedicine encounter.

F. Distance or Geography Restrictions

Distance restrictions are measured in miles and designate the amount of distance necessary between a distance site provider and patient as a condition of payment for telemedicine.

Geography is classified as rural, urban, metropolitan statistical area (MSA), defined population size, or health professional shortage area (HPSA).

We measured components of state Medicaid policies that apply distance or geography restrictions for conditions of coverage and payment when telemedicine is performed.

Over the past year, states have made considerable efforts to rescind mileage requirements for covered telemedicine services. Nevada and Oklahoma now offer telemedicine state-‐wide, while Iowa successfully removed its distance requirements. New Hampshire adopted legislation that includes geographically restricted language similar to Medicare. Indiana has statutory authority to remove their mileage requirements for all distance site providers but chooses to enforce the mileage requirement for some eligible providers. Earlier this year, Ohio Medicaid approved a regulation that would expand coverage of telemedicine services, and includes a five mile distance restriction as a condition of payment.

Eighty-‐six percent of the states cover telemedicine services state-‐wide without distance restrictions or geographic designations (Figure 10). This evidence dispels the misconception that telemedicine is only appropriate for rural settings only.

G. Eligible Providers

Most states allow physicians to perform telemedicine encounters within their scope of practice.

We measured components of state Medicaid policies that, for conditions of coverage and payment, broaden or restrict the types of distant site providers allowed to perform the telemedicine encounter. The following providers are observed as qualified health care professionals for covered telemedicine-‐provided services:

- physician (MD and DO)

- podiatrist

- chiropractor

- optometrist

- genetic counselor

- dentist

- physician assistant (PA)

- nurse practitioner (NP)

- registered nurse

- licensed practical nurse

- certified nurse midwife

- clinical nurse specialist

- psychologist

- marriage and family therapist

- clinical social worker (CSW)

- clinical counselor

- behavioral analyst

- substance abuse/addictions specialist

- clinical therapist

- pharmacist

- physical therapist

- occupational therapist

- speech-‐language pathologist and audiologist

- registered dietitian/nutritional professional

- diabetes/asthma/nutrition educator

- home health aide

- home health agency (HHA)

- FQHC

- CAH

- RHC

- CMHC

Each state received two (2) points for designating a physician, and one (1) point for each additional eligible provider authorized to provide covered telemedicine services. Those states that did not specify an eligible provider were given the maximum score possible (35).

Sixteen states and D.C. do not specify the type of health care provider allowed to provide telemedicine as a condition of payment (Figure 11).

Other interesting trends include Alaska, California, and Illinois which cover services when provided by a podiatrist. Alaska, California, and Kentucky cover services when provided by a chiropractor. California, Kentucky, and Washington are the only states to specify coverage for services when provided by an optometrist, while Arizona, California, and New York will cover services provided by a dentist. Although CMS has issued guidance clarifying their position on coverage for services related to autism spectrum disorder, only New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Washington specify coverage for telemedicine when provided by behavioral analysts. This trend is unique because these specialists are critical for the treatment of autism spectrum disorders. New Mexico, Oklahoma, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming specify coverage for telemedicine when provided by a substance abuse or addiction specialist.

Eighteen states ranked the lowest with failing (F) scores for authorizing less than nine health provider types. Florida, Idaho, and Montana ranked the lowest with coverage for physicians only.

H. Physician-‐provided Telemedicine Services

Physician-‐provided telemedicine services are commonly covered and reimbursed by Medicaid health plans. However, some plans base coverage on a prescribed set of health conditions or services, place restrictions on patient or provider settings, the frequency of covered telemedicine encounters, or exclude services performed by other medical professionals.

For this report, we measured components of state Medicaid policies that broaden or restrict a physician’s ability to use telemedicine for conditions of coverage and payment.

Eleven states and D.C. rank the highest for coverage of telemedicine-‐provided physician services (Figure 12). These states have no restrictions on service coverage or additional conditions of payment for services provided via telemedicine. Additionally, these states also allow a physician assistant and/or advanced practice nurse as eligible distant site providers.

Moreover, most states cover an office visit or consultations, with ultrasounds and echocardiograms being the least covered telemedicine-‐provided services.

The lowest ranking states, which scored an F, are Connecticut and Rhode Island which have no coverage for telemedicine under their Medicaid plans and Iowa and Ohio with limited service coverage and other arbitrary restrictions.

I. Mental and Behavioral Health Services

According to ATA’s telemental health practice guidelines, telemental health consists of the practice of mental health specialties at a distance using video-‐conferencing. The scope of services that can be delivered using telemental health includes: mental health assessments, substance abuse treatment, counseling, medication management, education, monitoring, and collaboration. Forty-‐eight states have some form of coverage and reimbursement for mental health provided via telemedicine video-‐conferencing. While the number of states with coverage in this area suggests enhanced access to mental health services, it is important to note that state policies for telemental health vary in specificity and scope.

We measured components of state Medicaid policies that broaden or restrict the types of providers allowed to perform the telemedicine encounter, telemedicine coverage for mental and behavioral health services.

Generally the telemedicine-‐provided services that are most often covered under state Medicaid plans include mental health assessments, individual therapy, psychiatric diagnostic interview exam, and medication management. Twelve states and D.C. rank the highest for coverage of mental and behavioral health services (Figure 13). These states have no restrictions on service coverage or additional conditions of payment for services provided via telemedicine.

Additionally, these states also classify at least one other medical professional (i.e. physician assistant and advanced practice nurse) as an eligible distant site provider.

It is also more common for states with telemental health coverage to allow physicians that are psychiatrists, advanced practice nurses with clinical specialties, and psychologists to perform the telemedicine encounter. However, many states allow non-‐medical providers to perform and reimburse for the telemedicine encounter. States including Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia and Wyoming cover telemedicine when performed by a licensed social worker. Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Indiana, Kentucky, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma,

Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming cover telemedicine when provided by a licensed professional counselor.

Further, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Washington are the only states to specify coverage for telemedicine when provided by behavioral analysts. This trend is unique because these specialists are critical for the treatment of autism spectrum disorders.

The lowest ranking states, which scored an F, are Connecticut and Rhode Island which have no coverage for telemedicine under their Medicaid plans. Iowa improved their grade from an ‘F’ to ‘B’ due to expanded service coverage offered through a contracted plan.

J. Rehabilitation Services

The ATA telerehabilitation guidelines define telerehabilitation as the “delivery of rehabilitation services via information and communication technologies. Clinically, this term encompasses a range of rehabilitation and habilitation services that include assessment, monitoring, prevention, intervention, supervision, education, consultation, and counseling”. Rehabilitation professionals utilizing telerehabilitation include: neuropsychologists, speech-‐language pathologists, audiologists, occupational therapists, and physical therapists.

We measured components of state Medicaid policies that broaden or restrict the types of providers allowed to perform the telemedicine encounter, restrictions on patient or provider settings, and coverage for telerehabilitation services.

Only 37 states were analyzed, scored and ranked for this indicator. Thirteen states and D.C. do not cover rehabilitation services for their Medicaid recipients. Although state policies vary in scope and application, 17 states are known to reimburse for telerehabilitative services in their Medicaid plans. Of those, 11 states rank the highest with telemedicine coverage for therapy services (Figure 14).

Further, of the 25 states that cover home telemedicine, only Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, and Tennessee reimburse for telerehabilitative services within the home health benefit.

K. Home Health Services

One well-‐proven form of telemedicine is remote patient monitoring. Remote patient monitoring may include two-‐way video consultations with a health provider, ongoing remote measurement of vital signs or automated or phone-‐based check-‐ups of physical and mental well-‐being. The approach used for each patient should be tailored to the patient’s needs and coordinated with the patient’s care plan.

For this report, we measured components of state Medicaid policies that broaden or restrict the types of providers allowed to perform the telemedicine encounter and services covered for home health services.

Alaska is the only state with the highest ranking for telemedicine provided services under the home health benefit (Figure 15).

Of the 25 states that cover home telemedicine, only Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, and Tennessee reimburse for telerehabilitative services within the home health benefit. Additionally, Pennsylvania is the only state that will cover telemedicine in the home when provided by a caregiver.

Arizona no longer covers telemedicine under their home health benefit. Seventy percent of the country ranked the lowest with failing (F) scores due to a lack of telemedicine services covered under the home health benefit.

L. Informed Consent

We measured components of state Medicaid and medical licensing board policies that apply more stringent requirements for telemedicine as opposed to in-‐person services. States were evaluated based on requirements for written or verbal informed consent, or unspecified methods of informed consent before a telemedicine encounter can be performed.

Of the 27 states with informed consent requirements, 19 states have such requirements imposed by their state Medical Board (Figure 16). Although their Medicaid programs do not cover telehealth, Rhode Island and Connecticut’s Medical Boards require informed consent.

M. Telepresenter

We measured components of state Medicaid and medical licensing board policies that apply more stringent requirements for telemedicine as opposed to in-‐person services. States were evaluated based on requirements for a telepresenter or health care provider on the premises during a telemedicine encounter.

Alabama, Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, and West Virginia only require a health care provider to be on the premises and not physically with the patient during a telemedicine encounter (Figure 17). Although Connecticut and Rhode Island have no telemedicine coverage under Medicaid, their Medical Boards do not require a telepresenter for telemedicine related services.

Innovative Payment or Service Delivery Models

This report also includes a category to capture innovative payment and service delivery models implemented in each state. In addition to state supported networks in specialty care and correctional health, the report identifies a few federally subsidized programs and waivers that states have leveraged to enhance access to health care services using telemedicine.

Over the years, states have increasingly used managed care organizations (MCOs) to create payment and delivery models involving capitated payments to provide better access to care and follow-‐up for patients, and also to control costs. The variety of payment methods and other operational details among Medicaid managed care arrangements is a useful laboratory for devising, adapting and advancing long-‐term optimal health delivery. MCOs experimenting with innovative delivery models including medical homes and dual-‐eligible coordination have incorporated telemedicine as a feature of these models especially because it helps to reduce costs related to emergency room use and hospital admissions.

Twenty-‐four states authorize telemedicine-‐provided services under their Medicaid managed care plans. Most notably, Massachusetts and New Hampshire offer coverage under select managed care plans but not under FFS.

The federal Affordable Care Act (ACA) offers states new financing and flexibility to expand their Medicaid programs, as well as to integrate Medicare and Medicaid coverage for dually eligible beneficiaries (“duals”). Michigan, New York and Virginia are the only states that extend coverage of telemedicine-‐provided services to their dual eligible population through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Capitated Financial Alignment Model for Medicare-‐Medicaid Enrollees.6

The ACA also includes a health home option to better coordinate primary, acute, behavioral, and long-‐term and social service needs for high-‐need, high-‐cost beneficiaries. The chronic conditions include mental health, substance use disorder, asthma, diabetes, heart disease, overweight (body mass index over 25), and other conditions that CMS may specify.

Nineteen states have approved health home state plan amendments (SPAs) from CMS.7 Alabama, Iowa, Maine, New York, Ohio, and West Virginia are the only states that have incorporated some form of telemedicine into their approved health home proposals.

Medicaid plans have several options to cover remote patient monitoring, usually under a federal waiver such as the Home and Community-‐based Services (HCBS) under Social Security Act section 1915(c).8 States may apply for this waiver to provide long-‐term care services in home and community settings rather than institutional settings. Kansas, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina are the only states that have used their waivers to provide telemedicine to beneficiaries in the home, specifically for the use of home remote patient monitoring.

State Report Cards

Appendix

References

1 Thomas, L. & Capistrant, G. American Telemedicine Association. “State Telemedicine Gaps Analysis” September 2014.

2 ATA State Policy Toolkit, 2015.

3 215 ILCS 5/356z.22; http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/documents/021500050K356z.22.htm

4 MCL Ch. 175 section 47BB; https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleXXII/Chapter175/Section47BB

5 Medicaid Benefits -‐ Physical Therapy and Other Services. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2012.

6 CMS tests models with States to better align the financing of Medicare and Medicaid programs and integrate primary, acute, behavioral health and long-‐term services and supports for their Medicare-‐Medicaid enrollees. For the Capitated Model, a state, CMS, and a health plan enter into a three-‐way contract, and the plan receives a

prospective blended payment to provide comprehensive, coordinated care; http://www.cms.gov/Medicare-‐ Medicaid-‐Coordination/Medicare-‐and-‐Medicaid-‐Coordination/Medicare-‐Medicaid-‐Coordination-‐ Office/FinancialAlignmentInitiative/CapitatedModel.html

7 Medicaid.gov, 2015; https://www.medicaid.gov/state-‐resource-‐center/medicaid-‐state-‐technical-‐ assistance/health-‐homes-‐technical-‐assistance/downloads/hh-‐map_v51.pdf

8 Medicaid.gov, 2015; http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-‐CHIP-‐Program-‐Information/By-‐Topics/Waivers/Home-‐ and-‐Community-‐Based-‐1915-‐c-‐Waivers.html

9 AL Medicaid Management Information System Provider Manual, Chapter–28 Physicians, p. 17;

http://medicaid.alabama.gov/CONTENT/6.0_Providers/6.7_Manuals/6.7.1_Provider_Manuals_2015/6.7.1.2_April_ 2015.aspx

10 AL Medicaid Management Information System Provider Manual, Chapter–105 Rehabilitative Services: DHR, DYS,

DPH, DMH, p. 11;

http://medicaid.alabama.gov/documents/6.0_Providers/6.7_Manuals/6.7.1_Provider_Manuals_2015/6.7.1.2_Apri l_2015/Apr15_105.pdf

11 AL Medicaid Management Information System Provider Manual, Chapter–39 Patient 1st Billing Manual, p. 32;

http://medicaid.alabama.gov/documents/6.0_Providers/6.7_Manuals/6.7.1_Provider_Manuals_2015/6.7.1.2_Apri l_2015/Apr15_39.pdf

12 AL Medicaid Agency, Amendment to Alabama State Plan for Medical Assistance (PN-‐11-‐10), May 2011;

http://www.alabamaadministrativecode.state.al.us/UpdatedMonthly/AAM-‐MAY-‐11/MISC.PDF

13 AL Medicaid Patient 1st In-‐Home Monitoring Program; January 2011;

http://medicaid.alabama.gov/documents/4.0_Programs/4.4_Medical_Services/4.4.10_Patient_1st/4.4.10_In_Hom e_Monitoring_Revised_1-‐24-‐11.pdf

14 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section II–School-‐Based Services, Policies and Procedures;

http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/sbs/sbs.htm

15 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section I: Physician, Advanced Nurse Practitioner & Physician Assistant Services; http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/physician/physician.htm

16 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section II–Podiatry Services, Policies and Procedures; http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/podiatry/podiatry.htm

17 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section II–Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and

Treatment Services, Policies and Procedures; http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/epsdt/epsdt.htm

18 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section II–Tribal Facility Services, Policies and Procedures; http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/tribal/tribal.htm

19 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section II–Hospice Services, Policies and Procedures; http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/docs/dnld/BillingManual_Hospice.pdf

20 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section II–Nutrition Services, Policies and Procedures;

http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/docs/dnld/BillingManual_Nutrition.pdf

21 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section II–Chiropractor Services, Policies and Procedures; http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/docs/dnld/BillingManual_Chiropractic.pdf

22 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section II–Community Behavioral Health Services, Policies and Procedures; http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/cbhs/cbhs.htm

23 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telemental and Behavioral Health. August

2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/ata-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐telemental-‐and-‐ behavioral-‐health.pdf?sfvrsn=10

24 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section II–Therapy Services, Policies and Procedures;

http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/therapies/therapies.htm

25 Alaska Medical Assistance Provider Billing Manual, Section II–Home Health Services, Policies and Procedures; http://manuals.medicaidalaska.com/docs/dnld/BillingManual_HomeHealth.pdf

26 ARS 20-‐841.09; http://www.azleg.gov/FormatDocument.asp?inDoc=/ars/20/00841-‐

09.htm&Title=20&DocType=ARS

27 AZ Health Care Cost Containment System, AHCCCS Fee-‐For-‐Service Provider Manual, Chapter–10 Professional

and Technical Services, p. 41; http://www.azahcccs.gov/commercial/Downloads/FFSProviderManual/FFS_Chap10.pdf

28 AHCCCS Telehealth Training Manual; http://www.azahcccs.gov/commercial/Downloads/IHS-‐

TribalManual/IHSTelehealthTrainingManual.pdf

29 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Store and Forward Telemedicine. July 2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐store-‐and-‐forward-‐ telemedicine.pdf?sfvrsn=10

30 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telestroke. January 2014;

http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐ telestroke.pdf?sfvrsn=8

31 Arizona Telemedicine Program; http://telemedicine.arizona.edu/

32 AHCCCS Medical Policy Manual, Chapter 300-‐Medical Policy for Covered Services, p.21; http://www.azahcccs.gov/shared/Downloads/MedicalPolicyManual/Chap300.pdf

33 Arkansas Medicaid, Physician/Independent lab/CRNA/Radiation Therapy Center-‐Section II, p. 34; https://www.medicaid.state.ar.us/Download/provider/provdocs/Manuals/PHYSICN/PHYSICN_II.doc

34 Arkansas Medicaid, Rehabilitative Services for Persons with Mental Illness-‐Section II, p. 14; https://www.medicaid.state.ar.us/InternetSolution/Provider/docs/rspmi.aspx

35 University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences – ANGELS Program; http://angels.uams.edu/

36 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telehealth for High-‐risk Pregnancy. January 2014; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐telehealth-‐for-‐ high-‐risk-‐pregnancy.pdf?sfvrsn=6

37 CA Insurance Code Sec. 10110 -‐ 10127.19; http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=INS§ionNum=10123.85 38 AB 1310; http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/cgi-‐bin/postquery?bill_number=ab_1310&sess=1314&house=A 39 AB 1771; http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/cgi-‐bin/postquery?bill_number=ab_1771&sess=1314&house=A 40 AB 1174; http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/cgi-‐bin/postquery?bill_number=ab_1174&sess=1314&house=A

41 CA Department of Health Care Services, Medi-‐Cal Part 2 General Medicine Manual, Telehealth, http://files.medi-‐ cal.ca.govpublications/masters-‐mtp/part2/mednetele_m01o03.doc

42 Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Telehealth Billing Recorded Webinar, September 2013.

43 CA Welfare and Institutions Code Sec. 14132.72; http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=WIC§ionNum=14132.72. 44 CA Welfare and Institutions Code Sec. 14132.725;

http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=WIC§ionNum=14132.725.

45 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Store and Forward Telemedicine. July 2013;

http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐store-‐and-‐forward-‐ telemedicine.pdf?sfvrsn=10

46 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telemental and Behavioral Health. August 2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/ata-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐telemental-‐and-‐ behavioral-‐health.pdf?sfvrsn=10

47 California Telehealth Network; http://www.caltelehealth.org/

48 CO Revised Statutes 10-‐16-‐123

49 10 CCR 2505-‐10.15

50 CO Revised Statutes 25.5-‐5-‐321

51 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Remote Patient Monitoring and Home Video

Visits. July 2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐ remote-‐patient-‐monitoring-‐and-‐home-‐video-‐visits.pdf?sfvrsn=6

52 CA Department of Health Care Services, Medi-‐Cal Part 2 General Medicine Manual, Telehealth, http://files.medi-‐

cal.ca.govpublications/masters-‐mtp/part2/mednetele_m01o03.doc

53 Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Telehealth Billing Recorded Webinar, September 2013.

54 California Telehealth Network; http://www.caltelehealth.org/

55 California Telehealth Network; http://www.caltelehealth.org/

56 ATA State Telemedicine Matrix 2015; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐ legislation-‐matrix-‐as-‐of-‐4-‐28-‐2015A6D18E449A99.pdf?sfvrsn=4

57 Medicaid Rates for Home Health Care Working Group;

https://www.cga.ct.gov/hs/taskforce.asp?TF=20151008_Medicaid%20Rates%20for%20Home%20Health%20Care% 20Working%20Group

58 Conn. Gen. Stat. Sec. 17b-‐245c;

http://search.cga.state.ct.us/dtsearch_pub_statutes.asp?cmd=getdoc&DocId=13656&Index=I%3a\zindex\surs&Hit Count=2&hits=190+191+&hc=2&req=%28number+contains+17b-‐245c%29&Item=0

59 2015 Delaware State Legislative Session; HB 69 -‐

http://www.legis.delaware.gov/LIS/LIS148.NSF/db0bad0e2af0bf31852568a5005f0f58/bae11c3e3516baa085257e3 5006685bb?OpenDocument

60 19 DE Reg.191;

http://regs.cqstatetrack.com/info/get_text?action_id=763841&text_id=766299&type=action_text

61 DC Code Sec. 31-‐3861

62 DC Code Sec. 31-‐3863

63 AGENCY FOR HEALTH CARE ADMINISTRATION Notice of Development of Rulemaking 59G-‐1.057; https://www.flrules.org/gateway/readFile.asp?sid=1&tid=16726988&type=1&file=59G-‐1.057.doc

64 Florida Medicaid, PRACTITIONER SERVICES COVERAGE AND LIMITATIONS HANDBOOK, Chapter-‐2, p.120;

http://portal.flmmis.com/FLPublic/Portals/0/StaticContent/Public/HANDBOOKS/Practitioner%20Services%20Hand book_Adoption.pdf

65 OCGA § 33-‐24-‐56.4

66 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: School-‐based Telehealth. July 2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐school-‐based-‐

telehealth.pdf?sfvrsn=8

67 Georgia Medicaid Telemedicine Handbook; https://www.mmis.georgia.gov/portal/Portals/0/StaticContent/Public/ALL/HANDBOOKS/Telemedicine%20Handbo ok%20OCT%202015%2001-‐10-‐2015%20180926.pdf

68 California Telehealth Network; http://www.caltelehealth.org/

69 HI Revised Statutes § 431:10A-‐116.3

70 SB 2469 – 27th Legislature;

http://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/measure_indiv.aspx?billtype=SB&billnumber=2469&year=2014 71 National Conference of State Legislatures. State Employee Health Benefits; http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-‐employee-‐health-‐benefits-‐ncsl.aspx#Self-‐fund

72 HI Administrative Rules §17-‐1737-‐51.1; http://humanservices.hawaii.gov/wp-‐content/uploads/2013/10/HAR-‐17-‐

1737-‐Scope-‐Contents-‐of-‐the-‐fee-‐for-‐service-‐medical-‐assistant-‐program.pdf

73 IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND WELFARE NOTICE OF RULEMAKING -‐ PROPOSED RULE 16-‐0309-‐1502;

http://adminrules.idaho.gov/bulletin/2015/10.pdf

74 CA Department of Health Care Services, Medi-‐Cal Part 2 General Medicine Manual, Telehealth, http://files.medi-‐ cal.ca.govpublications/masters-‐mtp/part2/mednetele_m01o03.doc

75 Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Telehealth Billing Recorded Webinar, September 2013.

76 CA Welfare and Institutions Code Sec. 14132.72; http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=WIC§ionNum=14132.72. 77 The Path to Transformation: Illinois § 1115 Waiver Proposal;

http://www2.illinois.gov/hfs/PublicInvolvement/1115/Pages/1115.aspx

78 SB 647 – 98th General Assembly;

http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/BillStatus.asp?DocNum=647&GAID=12&DocTypeID=SB&SessionID=85&GA=98 79 ATA State Telemedicine Matrix 2016; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐ legislation-‐matrix_2016147931CF25A6.pdf?sfvrsn=2

80 320 ILCS 42/20; http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/ilcs3.asp?ActID=2630&ChapterID=31

81 CA Department of Health Care Services, Medi-‐Cal Part 2 General Medicine Manual, Telehealth, http://files.medi-‐ cal.ca.govpublications/masters-‐mtp/part2/mednetele_m01o03.doc

82 Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Telehealth Billing Recorded Webinar, September 2013.

83 CA Welfare and Institutions Code Sec. 14132.72; http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=WIC§ionNum=14132.72.

84 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telemental and Behavioral Health. August

2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/ata-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐telemental-‐and-‐ behavioral-‐health.pdf?sfvrsn=10

85 IN State Legislative Session 2015 HB 1269; https://iga.in.gov/static-‐

documents/e/f/4/c/ef4c65a0/HB1269.05.ENRH.pdf

86 IC 12-‐15-‐5-‐11; https://iga.in.gov/legislative/laws/2015/ic/titles/012/articles/015/chapters/005/ 87 20140326-‐IR; http://www.in.gov/legislative/iac/20140326-‐IR-‐405140102ONA.xml.pdf

88 Indiana Health Coverage Programs Provider Manual, Chapter-‐8 Section 3, p.139; http://provider.indianamedicaid.com/ihcp/manuals/chapter08.pdf

89 IA State Legislative Session 2015 Act Chapter 137;

http://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/publications/iactc/86.1/CH0137.pdf

90 IAC 441—78.55(249A); https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/aco/arc/2166C.pdf

91 ATA State Telemedicine Matrix 2015; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐ legislation-‐matrix-‐as-‐of-‐4-‐28-‐2015A6D18E449A99.pdf?sfvrsn=4

92 Iowa Health Home State Plan Amendment for Adults and Children with Severe and Persistent Mental Illness;

http://www.medicaid.gov/State-‐Resource-‐Center/Medicaid-‐State-‐Technical-‐Assistance/Health-‐Homes-‐Technical-‐ Assistance/Downloads/IOWA-‐Approved-‐2nd-‐HH-‐SPA-‐.pdf

93 Dept. of Health and Environment, Kansas Medical Assistance Program, Provider Manual, Home Health Agency, p.

33 (Jan. 2013)

94 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Remote Patient Monitoring and Home Video Visits. July 2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐ remote-‐patient-‐monitoring-‐and-‐home-‐video-‐visits.pdf?sfvrsn=6

95 KY Revised Statutes § 304.17A-‐138

96 KY Revised Statutes § 205.559

97 907 KAR 3:170

98 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telerehabilitation. January 2014; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐ telerehabilitation.pdf?sfvrsn=6

99 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Managed Care and Telehealth. January 2014; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐managed-‐care-‐and-‐ telehealth.pdf?sfvrsn=6

100 HCR No. 88;

https://www.legis.la.gov%2Flegis%2FViewDocument.aspx%3Fd%3D898417&usg=AFQjCNEvK6diYXFnhdLdLiuqWnK Tw9-‐tvA&sig2=sjaC-‐9r0NOzFI-‐8M2OCuJA&cad=rja

101 LA Department of Health and Hospitals Report to House and Senate Committees on Health and Welfare,

January 20, 2013; http://www.dhh.louisiana.gov/assets/docs/LegisReports/HCR96-‐2013.pdf

102 HCR No. 88;

https://www.legis.la.gov%2Flegis%2FViewDocument.aspx%3Fd%3D898417&usg=AFQjCNEvK6diYXFnhdLdLiuqWnK Tw9-‐tvA&sig2=sjaC-‐9r0NOzFI-‐8M2OCuJA&cad=rja

103 LA Revised Statutes 22:1821

104 La. Admin. Code tit. 46, § 7507 and 7511

105 LA Dept. of Health and Hospitals, Professional Services Provider Manual, Chapter-‐5 Section 5.1

106 Maine State Plan Amendment, September 2015; http://www.medicaid.gov/State-‐resource-‐center/Medicaid-‐ State-‐Plan-‐Amendments/Downloads/ME/ME-‐15-‐007.pdf

107 ME Revised Statutes Annotated. Title 24 Sec. 4316

108 Maine Department of Health and Human Services Proposed Rule 2015-‐P211;

http://www.maine.gov/sos/cec/rules/notices/2015/111815.html

109 Maine Health Home State Plan Amendment; http://www.medicaid.gov/State-‐Resource-‐Center/Medicaid-‐State-‐ Plan-‐Amendments/Downloads/ME/ME-‐12-‐004-‐Att.pdf

110 Code of ME Rules. 10-‐144-‐101

111 MaineCare Benefits Manual, General Administrative Policies and Procedures, 10-‐144 Chapter-‐101, p. 20; http://www.maine.gov/sos/cec/rules/10/ch101.htm

112 Michael A. Edwards and Arvind C. Patel. Telemedicine Journal and e-‐Health. March 2003, 9(1): 25-‐39. 113 Maryland Register, Volume 42, Issue 21 Notice of Final Action [15-‐188-‐F];

http://www.dsd.state.md.us/MDR/4221/Assembled.htm

114 MD Insurance Code Annotated Sec. 15-‐139

115 Maryland Register, Volume 42, Issue 21 Notice of Final Action [15-‐188-‐F]; http://www.dsd.state.md.us/MDR/4221/Assembled.htm

116 Maryland Medical Assistance Program – Telemedicine 2014; https://mmcp.dhmh.maryland.gov/SitePages/Telemedicine%20Provider%20Information.aspx

117 ATA State Telemedicine Matrix 2015; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐

legislation-‐matrix-‐as-‐of-‐4-‐28-‐2015A6D18E449A99.pdf?sfvrsn=4

118 Boston Medical Center HealthNet Plan; http://www.bmchp.org/providers/claims/reimbursement-‐ policies

119 http://hnetalk.com/member/2015/08/01/health-‐new-‐england-‐introduces-‐

teladoc/?_ga=1.45474596.106012203.1447256463

120 http://www.fchp.org/providers/medical-‐

management/~/media/Files/ProviderPDFs/PaymentPolicies/TelemedicinePayPolicy.ashx

121 National Telenursing Center; http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/gov/departments/dph/programs/community-‐ health/dvip/violence/sane/telenursing/the-‐national-‐telenursing-‐center.html

122 Partners Telestroke Network; http://telestroke.massgeneral.org/phstelestroke.aspx

123 101 CMR 350; http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/eohhs/eohhs-‐regs/101-‐cmr-‐350-‐hha-‐redlined.pdf

124 MI Compiled Law Services Sec. 500.3476

125 Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Medical Services Administration 1518-‐SBS; www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/1518-‐SBS-‐P_487449_7.pdf

126 Medicare-‐Medicaid Capitated Financial Alignment Demonstration for Michigan; https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-‐Medicaid-‐Coordination/Medicare-‐and-‐Medicaid-‐Coordination/Medicare-‐ Medicaid-‐Coordination-‐Office/FinancialAlignmentInitiative/Downloads/MIMOU.pdf

127 Medicaid Policy Bulletin MSA 13-‐34; http://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/MSA_13-‐34_432621_7.pdf

128 MDCH Telemedicine Database January 2014; http://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/Telemedicine-‐ 012014_445921_7.pdf

129 Minnesota State Legislature 2015 Session Chapter 71;

https://www.revisor.mn.gov/laws/?year=2015&type=0&doctype=Chapter&id=71&format=pdf

130 MN Statute 254B.14; https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=254B.14

131 MN Dept. of Human Services, Provider Manual, Continuum of Care Pilot; http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/idcplg?IdcService=GET_DYNAMIC_CONVERSION&RevisionSelectionMethod=Lat

estReleased&dDocName=dhs16_194151

132 MN Statute Sec. 256B.0625; https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=256B.0625

133 MN Dept. of Human Services, Provider Manual, Physician and Professional Services; http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/idcplg?IdcService=GET_DYNAMIC_CONVERSION&RevisionSelectionMethod=Lat estReleased&dDocName=id_008926#Telemedicine

134 MN Dept. of Human Services, Provider Manual, Rehabilitative Services; http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/idcplg?IdcService=GET_DYNAMIC_CONVERSION&RevisionSelectionMethod=Lat

estReleased&dDocName=id_008951

135 MN Statute Sec. 256B.0653; https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=256B.0653

136 MS Code Sec. 83-‐9-‐351

137 SB 2646; http://billstatus.ls.state.ms.us/2014/pdf/history/SB/SB2646.xml

138 Miss. Admin. Code Part 225, Chapter 1; http://www.sos.ms.gov/ACProposed/00021320b.pdf

139 Mississippi Division of Medicaid, SPA 15-‐003 Telehealth Services; http://www.medicaid.ms.gov/wp-‐ content/uploads/2015/04/SPA-‐15-‐003.pdf

140 Code Miss. R. 30-‐5-‐2635;

http://www.msbml.ms.gov/msbml/web.nsf/webpages/Regulations_Regulations/$FILE/11-‐ 2013AdministrativeCode.pdf?OpenElement

141 MO Revised Statutes § 376.1900.1

142 MO Code of State Regulation, Title 13, 70-‐3.190

143 ATA State Telemedicine Matrix 2015; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐ legislation-‐matrix-‐as-‐of-‐4-‐28-‐2015A6D18E449A99.pdf?sfvrsn=4

144 MO HealthNet Provider Manuals – Physicians Section 13;

http://207.15.48.5/collections/collection_phy/Physician_Section13.pdf

145 MO Consolidated State Reg. 22:10-‐3.057

146 MO HealthNet Provider Manuals – Behavioral Health Section 13; http://207.15.48.5/collections/collection_psy/Behavioral_Health_Services_Section13.pdf

147 MO HealthNet Provider Manuals – Comprehensive Substance Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation Section 13; http://207.15.48.5/collections/collection_cst/CSTAR_Section13.pdf

148 MO HealthNet Provider Manuals – Comprehensive Substance Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation Section 19; http://207.15.48.5/collections/collection_cst/CSTAR_Section19.pdf

149 Missouri Telehealth Network; http://medicine.missouri.edu/telehealth/

150 MT Code Sec. 33-‐22-‐138

151 MT Dept. of Public Health and Human Services, Medicaid and Medical Assistance Programs Manual, Physician Related Services; http://medicaidprovider.hhs.mt.gov/pdf/manuals/physician07012014.pdf

152 NE State Legislature 2015 Session LB 257;

http://nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/Current/PDF/Slip/LB257.pdf

153 Nebraska State Plan Amendment, October 2014; http://dhhs.ne.gov/medicaid/Documents/3.1a.pdf

154 LB 254; http://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill.php?DocumentID=18716

155 Nebraska Statewide Telehealth Network; http://www.netelehealth.net/

156 Provider Manual; http://www.sos.ne.gov/rules-‐and-‐ regs/regsearch/Rules/Health_and_Human_Services_System/Title-‐471/Chapter-‐02.pdf

157 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: School-‐based Telehealth. July 2013;

http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐school-‐based-‐ telehealth.pdf?sfvrsn=8

158 Revised Statutes of NE. Sec. 71-‐8506

159 NMAP Services, 471 NAC 1-‐006

160 Proposed regulation, NMAP Services, 471 NAC 1-‐006; http://www.sos.ne.gov/rules-‐and-‐ regs/regtrack/proposals/0000000000001346.pdf

161 Nevada State Legislature 2015 Session Chapter 153;

http://www.leg.state.nv.us/Session/78th2015/Bills/AB/AB292_EN.pdf

162 Nevada Department of Business and Industry Division of Industrial Relations Medical Fee Schedule, August 2014; http://dirweb.state.nv.us/WCS/mfs/2015MedFeeSchedule.pdf

163 NV Dept. of Health and Human Services., Medicaid Services Manual, Section 3403.4

164 NH Revised Statutes Annotated, 415-‐J:3

165 New Hampshire General Court 2015 Session Chaptered Law 0206; http://www.gencourt.state.nh.us/legislation/2015/SB0112.pdf

166 Well Sense Health Plan; https://www.google.com/url?q=http://www.bmchp.org/app_assets/physician-‐non-‐

physician-‐reimbursement-‐policy-‐ nh_20131114t114633_en_web_452716bd5a7947b59381a6194af31713.pdf&sa=U&ei=FjrVU-‐q9G-‐m-‐ sQTg4YCQCg&ved=0CAYQFjAA&client=internal-‐uds-‐cse&usg=AFQjCNGBBItpApuMULB1o7VV9mAYi3KKdg

167 New Hampshire Healthy Families (Cenpatico);

http://www.nhhealthyfamilies.com/files/2012/01/NHHF_ProviderManual_REVFeb2014.pdf 168 New Jersey Individual Health Coverage Program; http://www.state.nj.us/dobi/division_insurance/ihcseh/ihcrulesadoptions.htm

169 New Jersey Small Employer Health Benefits Programs; http://www.state.nj.us/dobi/division_insurance/ihcseh/sehrulesadoptions.htm

170 ATA State Telemedicine Matrix 2015; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐ legislation-‐matrix-‐as-‐of-‐4-‐28-‐2015A6D18E449A99.pdf?sfvrsn=4

171 NJ Department of Human Services Division of Medical Assistance & Health Services, December 2013 Newsletter; www.njha.com/media/292399/Telepsychiatrymemo.pdf

172 NM Statute. 59A-‐22-‐49.3

173 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: School-‐based Telehealth. July 2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐school-‐based-‐ telehealth.pdf?sfvrsn=8

174 NMAC 8.310.2.9-‐M; http://www.nmcpr.state.nm.us/nmac/parts/title08/08.310.0002.htm

175 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telemental and Behavioral Health. August

2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/ata-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐telemental-‐and-‐ behavioral-‐health.pdf?sfvrsn=10

176 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telerehabilitation. January 2014;

http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐ telerehabilitation.pdf?sfvrsn=6

177 New Mexico Telehealth Alliance; http://www.nmtelehealth.org/

178 NMAC 8.308.9.18; http://www.nmcpr.state.nm.us/nmac/parts/title08/08.308.0009.htm

179 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Managed Care and Telehealth. January

2014; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐managed-‐care-‐ and-‐telehealth.pdf?sfvrsn=6

180 S07852 – General Assembly; http://open.nysenate.gov/legislation/bill/S7852-‐2013

181 A02552 – General Assembly;

http://assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?default_fld=&bn=A02552&term=2015&Summary=Y&Actions=Y&Text=Y&Votes=Y 182 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Remote Patient Monitoring and Home Video Visits. July 2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐

remote-‐patient-‐monitoring-‐and-‐home-‐video-‐visits.pdf?sfvrsn=6

183 Medicare-‐Medicaid Capitated Financial Alignment Demonstration for New York;

http://www.cms.gov/Medicare-‐Medicaid-‐Coordination/Medicare-‐and-‐Medicaid-‐Coordination/Medicare-‐Medicaid-‐ Coordination-‐Office/FinancialAlignmentInitiative/Downloads/VAMOU.pdf

184 New York Health Home State Plan Amendment for Individuals with Chronic Behavioral and Mental Health

Conditions; http://www.medicaid.gov/State-‐Resource-‐Center/Medicaid-‐State-‐Technical-‐Assistance/Health-‐Homes-‐ Technical-‐Assistance/Downloads/New-‐York-‐SPA-‐12-‐11.PDF

185 New York State Medicaid Program Update, Volume 31 Number 3 March 2015;

www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/program/update/2015/mar15_mu.pdf

186 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telestroke. January 2014;

http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐ telestroke.pdf?sfvrsn=8

187 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Managed Care and Telehealth. January

2014; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐managed-‐care-‐ and-‐telehealth.pdf?sfvrsn=6

188 ATA State Telemedicine Matrix 2015; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐ legislation-‐matrix-‐as-‐of-‐4-‐28-‐2015A6D18E449A99.pdf?sfvrsn=4

189 NC General Statutes Article 3, Ch. 143B, Sect. 12A.2B.(b)

190 NC Div. of Medical Assistance, Medicaid and Health Choice Manual, Clinical Coverage Policy No: 1H, Telemedicine and Telepsychiatry; http://www.ncdhhs.gov/dma/mp/1H.pdf

191 North Dakota Legislative Branch 2015 Session HB 1038; http://www.legis.nd.gov/assembly/64-‐

2015/documents/15-‐0079-‐05000.pdf

192 North Dakota State Plan Amendment, January 2012; http://www.medicaid.gov/State-‐resource-‐ center/Medicaid-‐State-‐Plan-‐Amendments/Downloads/ND/ND-‐11-‐007.pdf

193 ND Dept. of Human Services, General Information For Providers, Medicaid and Other Medical Assistance Programs; www.nd.gov/dhs/services/medicalserv/medicaid/docs/telemedicine-‐policy.pdf

194 ATA State Telemedicine Matrix 2015; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐ legislation-‐matrix-‐as-‐of-‐4-‐28-‐2015A6D18E449A99.pdf?sfvrsn=4

195 HB 123; http://www.legislature.state.oh.us/bills.cfm?ID=130_HB_123

196 OAC 5160-‐1-‐18

197 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: School-‐based Telehealth. July 2013;

http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐school-‐based-‐ telehealth.pdf?sfvrsn=8

198 Ohio Health Home State Plan Amendment; http://www.medicaid.gov/State-‐Resource-‐Center/Medicaid-‐State-‐

Plan-‐Amendments/Downloads/OH/OH-‐12-‐0013-‐HHSPA.pdf

199 OK Admin. Code Sec. 317:30-‐3-‐27; http://www.okhca.org/xPolicySection.aspx?id=7061&number=317:30-‐3-‐ 27.&title=Telemedicine

200 OK Statute, Title 36 Sec. 6803.

201 Oregon State Legislature 2015 Session Chapter 264; https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2011R1/Downloads/MeasureDocument/SB0144/Enrolled

202 OARS Sec. 743A.058

203 OARS 410-‐130-‐0610

204 ATA State Telemedicine Matrix 2015; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐ legislation-‐matrix-‐as-‐of-‐4-‐28-‐2015A6D18E449A99.pdf?sfvrsn=4

205 PA Dept. of Aging, Office of Long Term Aging, APD #09-‐01-‐05, Oct. 1, 2009; http://www.dpw.state.pa.us/cs/groups/webcontent/documents/document/d_007041.pdf

206 PA Department of Public Welfare, Medical Assistance Bulletin 09-‐12-‐31,31-‐12-‐31, 33-‐12-‐30, May 23, 2012;

http://www.dpw.state.pa.us/cs/groups/webcontent/documents/bulletin_admin/d_005993.pdf

207 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telehealth for High-‐risk Pregnancy. January

2014; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐telehealth-‐for-‐ high-‐risk-‐pregnancy.pdf?sfvrsn=6

208 ATA State Telemedicine Matrix 2015; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐

legislation-‐matrix-‐as-‐of-‐4-‐28-‐2015A6D18E449A99.pdf?sfvrsn=4

209 SC Community Choices (0405.R02.00); https://www.scdhhs.gov/historic/insideDHHS/Bureaus/BureauofLongTermCareServices/telemonitoring.html

210 SC Department of Mental Health Telepsychiatry Program; http://www.state.sc.us/dmh/telepsychiatry/

211 SC OB/GYN Telemedicine Demonstration Project; https://www.scdhhs.gov/press-‐release/obgyn-‐telemedicine-‐ demonstration-‐project

212 SC Health and Human Services Dept., Physicians Provider Manual; https://www.scdhhs.gov/internet/pdf/manuals/Physicians/Manual.pdf

213 Kevin Burbach. (2014, August 2). State to test telehealth drug treatment program. Argus Leader. Retrieved from

http://www.argusleader.com/story/news/local/2014/08/02/state-‐test-‐telehealth-‐drug-‐treatment-‐ program/13505693/

214 SD Medical Assistance Program, Professional Services Manual; http://dss.sd.gov/sdmedx/includes/providers/billingmanuals/docs/ProfessionalManual9.20.12.pdf 215 SD Dept. of Social Services, Dept. of Adult Services & Aging, Telehealth Technology;

http://dss.sd.gov/elderlyservices/services/telehealth.asp

216 SB 2050; http://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/Billinfo/default.aspx?BillNumber=SB2050&ga=108 217 Texas State Legislature 2015 Session HB 1878;

http://www.capitol.state.tx.us/tlodocs/84R/billtext/pdf/HB01878F.pdf#navpanes=0

218 TX Insurance Code, Title 8, Sec. 1455.004

219 Texas Medicaid Provider Procedures Manual, Volume 2;

http://www.tmhp.com/TMPPM/TMPPM_Living_Manual_Current/Vol2_Telecommunication_Services_Handbook.p df

220 TX Admin. Code, Title 1, Sec. 354.1434 and 355.7001

221 Utah State Bulletin, Volume 2015, Number 12 -‐ 06/15/2015; http://www.rules.utah.gov/publicat/bull_pdf/2015/b20150615.pdf 222 UT Admin. Code R414-‐42-‐2

223 Utah Medicaid Provider Manual: Home Health Agencies

224 Utah Telehealth Network; http://www.utahtelehealth.net/

225 UT Code Annotated Sec. 26-‐18-‐13 and UT Physician Medicaid Manual

226 UT Div. of Medicaid and Health Financing, Utah Medicaid Provider Manual, Mental Health Centers/Prepaid Mental Health Plans

227 Vermont General Assembly 2015 Session Act 54;

http://legislature.vermont.gov/assets/Documents/2016/Docs/ACTS/ACT054/ACT054%20As%20Enacted.pdf

228 VT Statutes Annotated, Title 8 Sec. 4100k

229 Dept. of VT Health Access, Provider Manual, Section 10.3.52

230 VA Code Annotated § 38.2-‐3418.16. Coverage for telemedicine services; https://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-‐ bin/legp504.exe?000+cod+38.2-‐3418.16

231 VA DMAS, Medicaid Provider Manual, Chapter–IV Physician/Practitioner, p. 19;

https://www.virginiamedicaid.dmas.virginia.gov/ECMPdfWeb/ECMServlet/Documentationmanuals/Phy4/chapterI V_phy

232 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telerehabilitation. January 2014; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐ telerehabilitation.pdf?sfvrsn=6

233 VA DMAS, Medicaid Provider Manual, Chapter–IV Local Education Agency, p. 11;

https://www.virginiamedicaid.dmas.virginia.gov/ECMPdfWeb/ECMServlet/Documentationmanuals/School4/chapt erIV_sd

234 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: School-‐based Telehealth. July 2013;

http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐school-‐based-‐ telehealth.pdf?sfvrsn=8

235 VA DMAS Medicaid Memo, May 13, 2014, Updates to Telemedicine Coverage;

https://www.virginiamedicaid.dmas.virginia.gov/ECMPdfWeb/ECMServlet?memospdf=Medicaid+Memo+2014.05. 13.pdf

236 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telestroke. January 2014;

http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐ telestroke.pdf?sfvrsn=8

237 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Telehealth for High-‐risk Pregnancy. January

2014; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐telehealth-‐for-‐ high-‐risk-‐pregnancy.pdf?sfvrsn=6

238 Virginia Telehealth Network; http://ehealthvirginia.org/

239 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Managed Care and Telehealth. January 2014; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐managed-‐care-‐and-‐

telehealth.pdf?sfvrsn=6

240 Medicare-‐Medicaid Capitated Financial Alignment Demonstration for Virginia; http://www.cms.gov/Medicare-‐

Medicaid-‐Coordination/Medicare-‐and-‐Medicaid-‐Coordination/Medicare-‐Medicaid-‐Coordination-‐ Office/FinancialAlignmentInitiative/Downloads/VAMOU.pdf

241 http://www.telemedicine.vcuhealth.org/

242 HB 1448 – 2013 and 2014 Regular Session; http://apps.leg.wa.gov/billinfo/summary.aspx?bill=1448&year=2013

243 WAC 182-‐531-‐1730 Telemedicine -‐ Emergency Rulemaking; http://apps.leg.wa.gov/documents/laws/wsr/2014/11/14-‐11-‐018.htm

244 WAC 182-‐531-‐1436 Applied behavior analysis (ABA)—Services provided via telemedicine -‐ Emergency Rulemaking; http://apps.leg.wa.gov/documents/laws/wsr/2014/02/14-‐02-‐056.htm

245 American Telemedicine Association, State Medicaid Best Practice: Remote Patient Monitoring and Home Video

Visits. July 2013; http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-‐source/policy/state-‐medicaid-‐best-‐practice-‐-‐-‐ remote-‐patient-‐monitoring-‐and-‐home-‐video-‐visits.pdf?sfvrsn=6

246 WA State Health Care Authority Apple Health, Medicaid Provider Manual, Physician-‐Related Services/Health

care Professional Services, p. 45; http://www.hca.wa.gov/medicaid/billing/Documents/guides/physician-‐ related_services_mpg.pdf

247 WA State Health Care Authority Apple Health, Medicaid Provider Manual, Home Health Services (Acute Care Services), p. 20; http://www.hca.wa.gov/medicaid/billing/documents/guides/home_health_services_bi.pdf 248 WV Department of Health and Human Services, Medicaid Provider Manual, Chapter–519.7.5.2 Practitioners

Services, p. 25; http://www.dhhr.wv.gov/bms/Documents/manuals_Chapter_519_Practitioners.pdf

249 WV Department of Health and Human Services, Medicaid Provider Manual, Chapter–502.13 Behavioral Health Clinic Services, p. 13; http://www.dhhr.wv.gov/bms/Documents/Chapter502_BHCS.pdf

250 WV Department of Health and Human Services, Medicaid Provider Manual, Chapter–503.13 Behavioral Health Rehabilitation Services., p. 13; http://www.dhhr.wv.gov/bms/Documents/Chapter503_BHRS.pdf

251 WV Department of Health and Human Services, Medicaid Provider Manual, Chapter–527.30.5.1.4 Mountain

Health Choices, p. 40; http://www.dhhr.wv.gov/bms/Documents/bms_manuals_Chapter_527MountainHealthChoices.pdf

252 West Virginia Health Home State Plan Amendment; https://www.medicaid.gov/state-‐resource-‐ center/medicaid-‐state-‐plan-‐amendments/downloads/wv/wv-‐14-‐0009.pdf

253 WI Forward Health, BadgerCare Plus and Medicaid Provider Manual, Topic #510,

https://www.forwardhealth.wi.gov/WIPortal/Online%20Handbooks/Print/tabid/154/Default.aspx?ia=1&p=1&sa=5 0&s=2&c=61&nt=Telemedicine

254 WY Equality Care, Medicaid Provider Manual, Chapter–6.24 General Provider Information, p. 6-‐62;

http://wyequalitycare.acs-‐inc.com/manuals/Manual_CMS%201500.pdf

255 Wyoming Telehealth Consortium; http://wyomingtelehealth.org/